Portrait of a Woman in Silk by Zara Anishanslin

Author:Zara Anishanslin

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780300220551

Publisher: Yale University Press

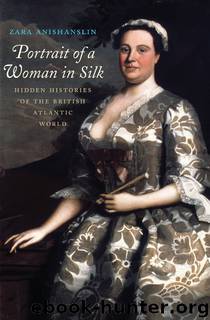

Joseph Highmore, Caroline Wilhelmina of Brandenburg-Ansbach, 1727 or after, mezzotint on paper, 11 1/4 in. × 8 1/8 in. D7913. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Willing’s social performance at the dancing assembly—her highly visible act of offering herself as partner to Hamilton—saved him from embarrassment, but it also made her reigning queen of the ball. Balls progressed with rigidly defined dance sets, each determined by the “lead woman.” The first dance, usually a minuet like that Hamilton danced with Willing, held particular importance in the order of things. Dancing manuals that described the etiquette of the dance often detailed the grandest of those affairs, the royal balls, as examples to which “all private balls ought to be conformable.” In those royal balls, dancers were placed in order of social hierarchy, with the king performing the first dance with the queen.22

Willing was not the only colonial woman to use the ball as a stage for performing ritualized maneuverings for power. Balls like those held by the Philadelphia Dancing Assembly were more than simply entertainment. They were also social contests in which women especially used comportment and fashion to compete for public recognition as superior in beauty, grace, and refinement. Dances like the one Willing performed with Hamilton emphasized refined grace, and the first dance of the night established the dancers’ standing and skill. This skill (or lack of it) became the subject of immediate gossip among the audience. Once the ball ended, letters like Richard Peters’s to Thomas Penn, diary entries, and more gossip made such chatter into reputation.23 In leading the first dance in such a “Genteel Manner,” Willing established her standing as the lead woman, or the queen, of the ball. The regal iconography referenced in Willing’s performance at the ball was a pervasive feature of colonial American culture.24

The life of colonist Hannah Garrett Lewis offers dramatic insight into how deeply such regal iconography—about women in the royal family like Queen Caroline and her daughters rather than simply the king—could penetrate the colonial imagination. In 1746, the same year Feke painted Anne Shippen Willing’s portrait, the Quakers of the Shippens’ meetinghouse, the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, recorded that one of their members, Hannah Garrett Lewis, “hath been for sometime past under Great Indisposition of Mind.”25 This indisposition manifested itself in Lewis’s steadfast assertion that “she was the eldest daughter of George the Second King of England, and Heir to his Throne.”26

Lewis became a notorious feature of the Philadelphia landscape. On one occasion, she served two unsuspecting women visitors cat for lunch. She often walked the streets, striding “valiantly with her broad sword, a silver cane which she would brandish against the trade boys, who often attacked her.” Eventually, Lewis was committed to Pennsylvania Hospital, “which she called her Palace,” and where she lived, she claimed, on “Tribute money” given her in London by “the King her father.” Careful of her regal splendor, at the hospital she abandoned her snuff addiction in favor of ground ginger, which would not stain her “cloaths.”

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15356)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14508)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12393)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12099)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12028)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5786)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5446)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5404)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5308)

Paper Towns by Green John(5191)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5008)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4964)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4504)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4490)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4447)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4390)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4348)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4325)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4199)